FISHING IN THE BOLIVIAN AMAZON:

Preface

In their long history as both a monument to nations’ cultural heritage, to serving as a pedagogical tool, museums have evolved from being inaccessible and distant to the public — where access was only limited to the “right sort” (Hudson 1987) — to being the cornerstone of showcasing a nation’s societal and cultural evolution. This essay seeks to explore on an exciting new possibility to recreating and preserving this heritage, in adapting and utilizing digital media in the 21st century.

3D Models

Figures

Figure 1: Introduction to use of indigenous technologies in fishing in the Bolivian Amazon (Brinkmeier and Erickson 2007: 1).

Figure 2: Intricate drawing of fish weirs, fish ponds and earthworks of a typical pre-Columbian landscape in the Bolivian Amazon (Brinkmeier and Erickson 2007: 6).

Figure 3: Fish trap from the Upper Xingu River (with inserted labels). Length of 74cm, upper diameter of 34cm, lower diameter of 40-45cm. Object 31-48-418 in the Penn Museum Object Database.

Figure 4: Fish trap from the Upper Xingu River. Length of 74cm, upper diameter of 34cm, lower diameter of 40-45cm. Object 31-48-418 in the Penn Museum Object Database.

Figure 5: Fish trap from the Upper Xingu River. Length of 74cm, upper diameter of 34cm, lower diameter of 40-45cm. Object 31-48-418 in the Penn Museum Object Database.

Figure 6: Fishing with the cóvo (Keller 1875: 100).

Figure 7: Artwork depicting the cóvo (left), strings of fish (probably buchere), and fish baskets (Mercado 1991: 137).

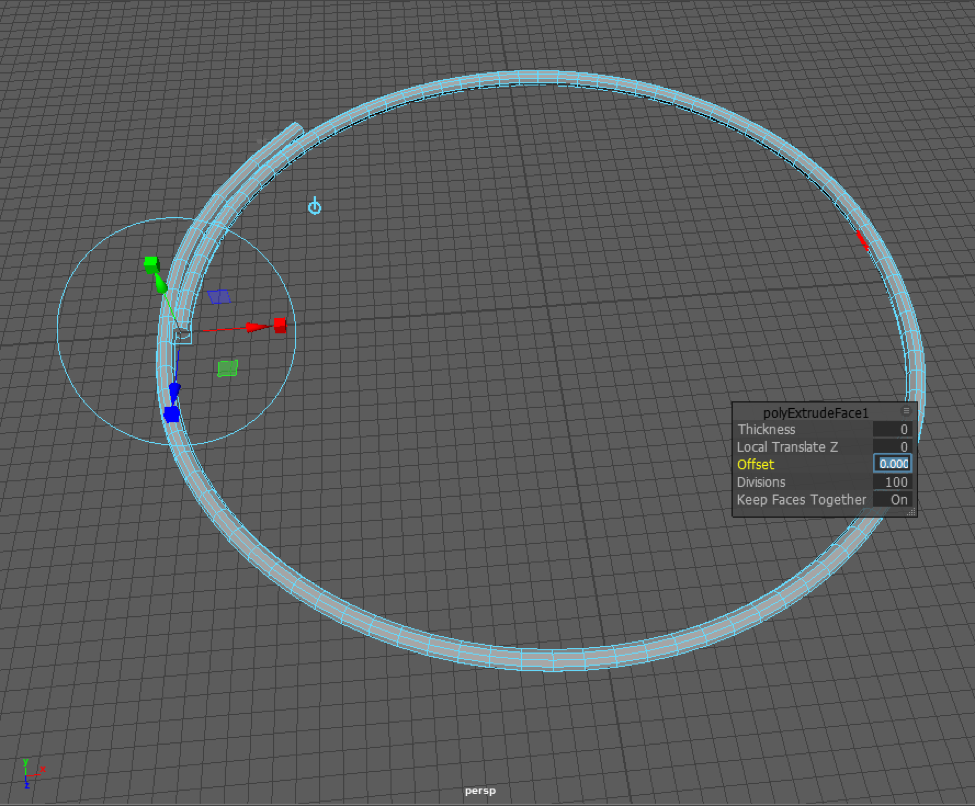

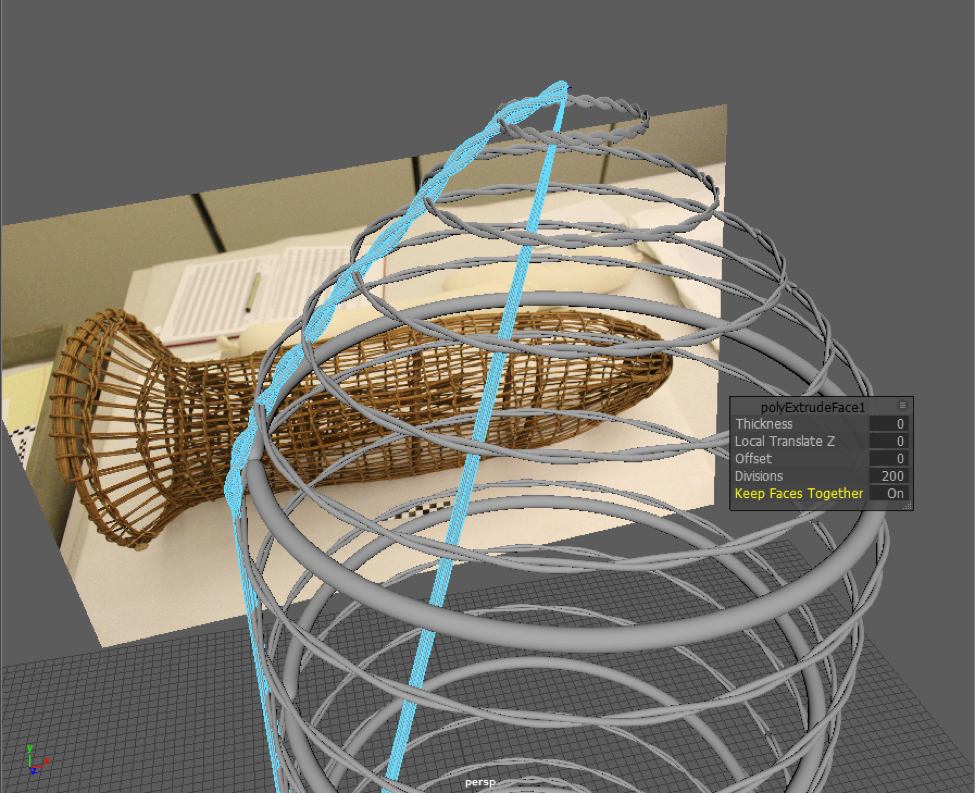

Figure 8: Construction of the base ring, with 42cm diameter.

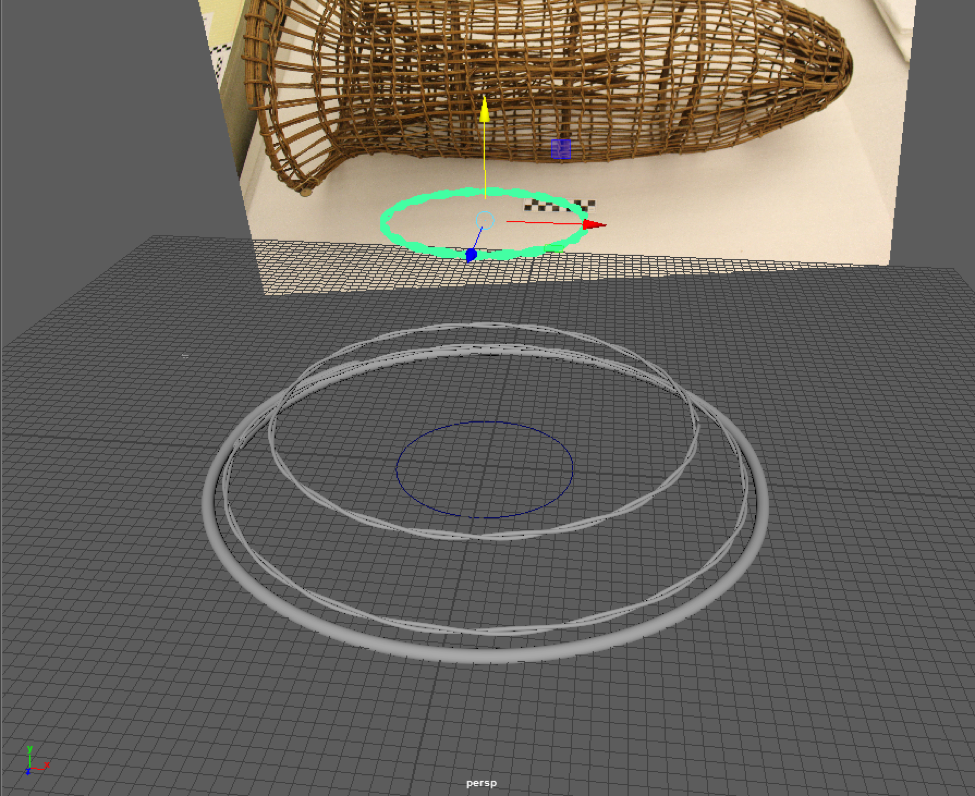

Figure 9: Extruded several twisted ring to form the inner funnel shape (from 40cm to 16cm in diameter).

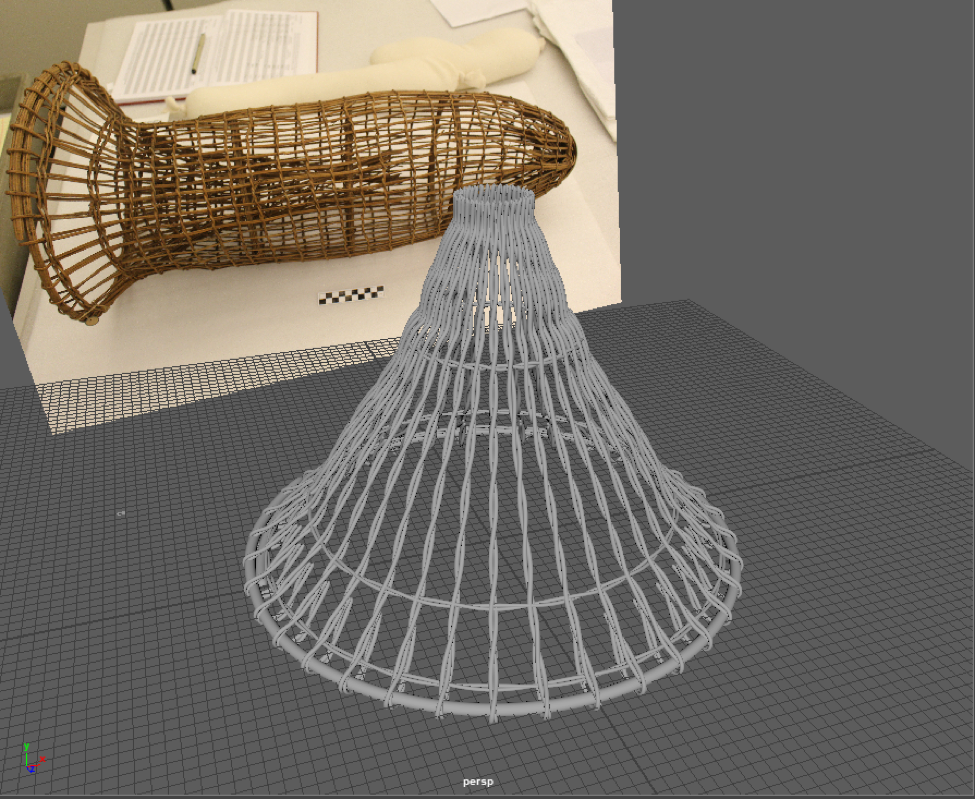

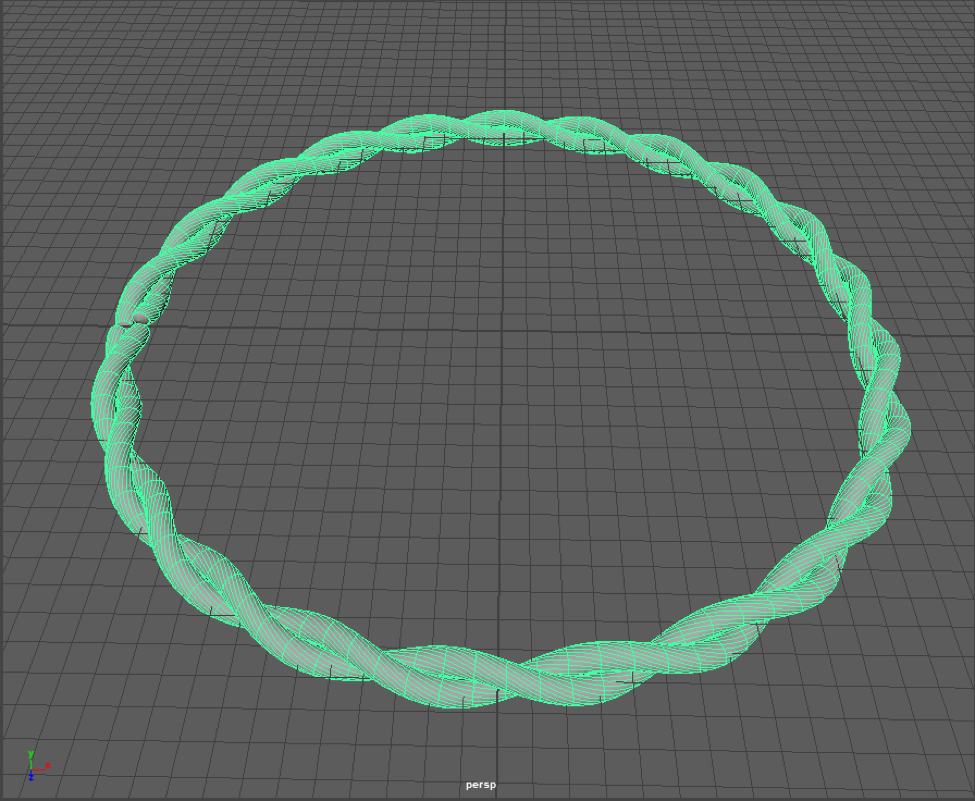

Figure 10: The completion of the inner funnel trap. The top of the loop was around 30cm off the ground.

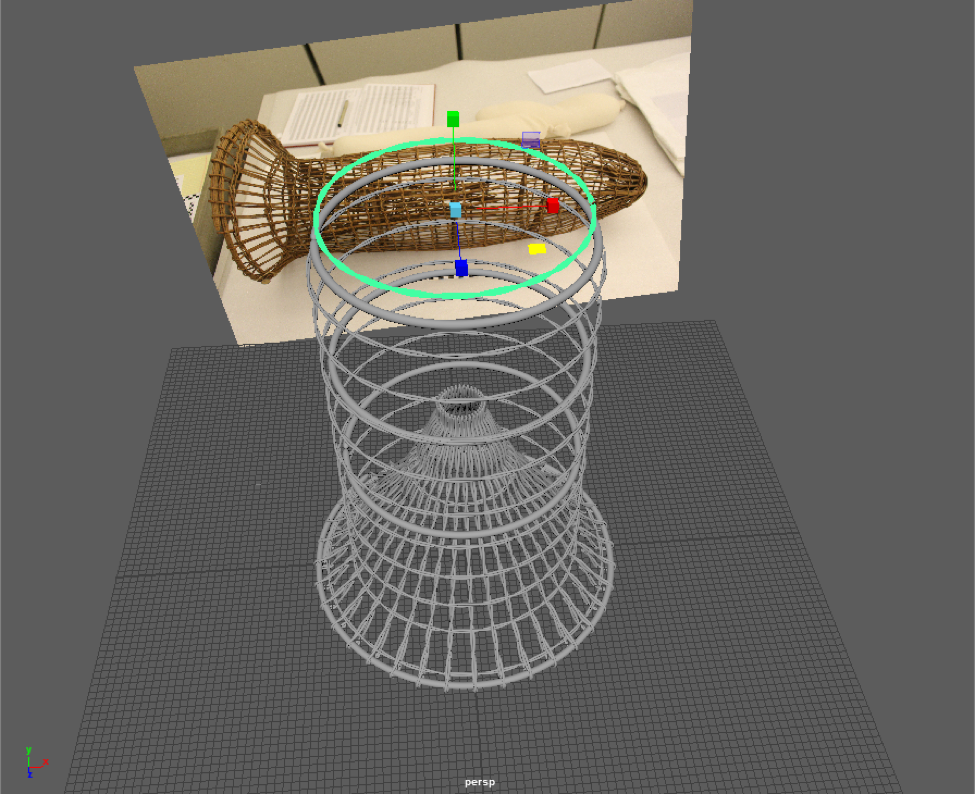

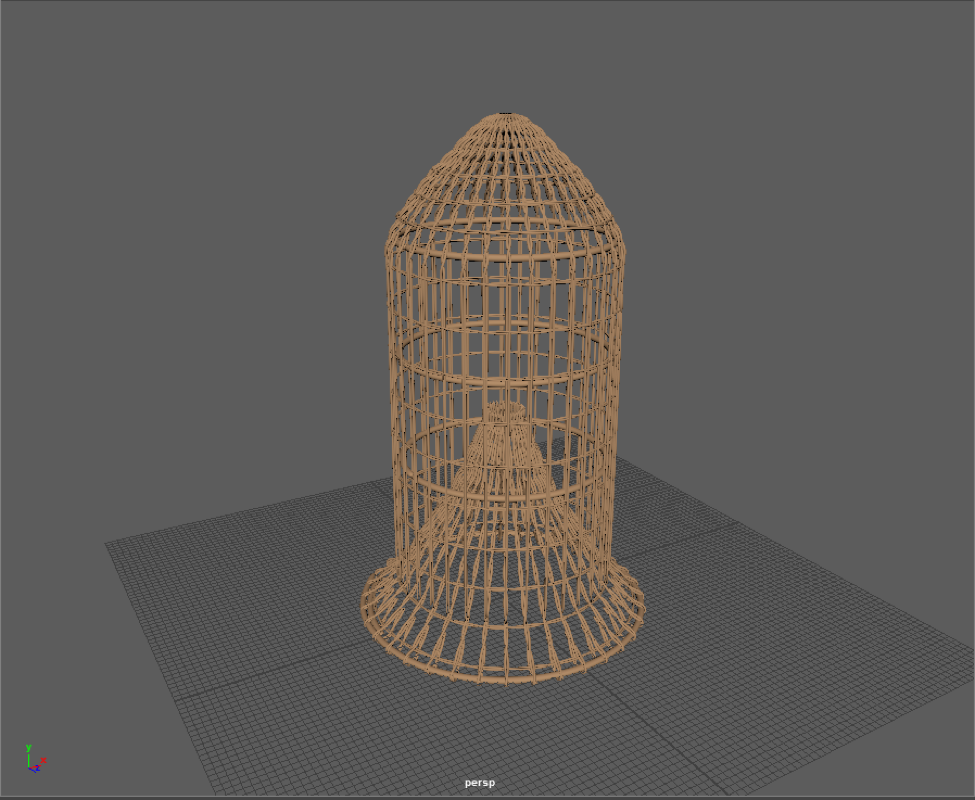

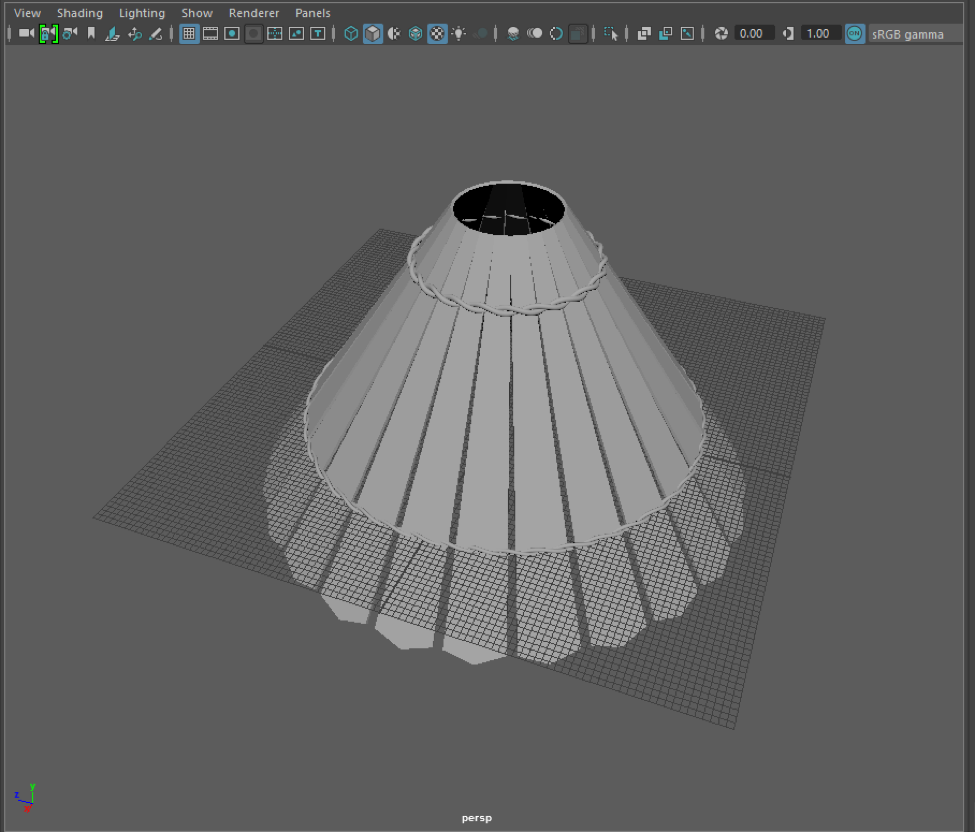

Figure 11: The addition of several concentric rings to form the outer portion of the trap. These extended up to 60cm in height, with a parabolic-rounding off at the end.

Figure 12: Creating the wrap around the outer shell.

Figure 13: The final textured version of the trap.

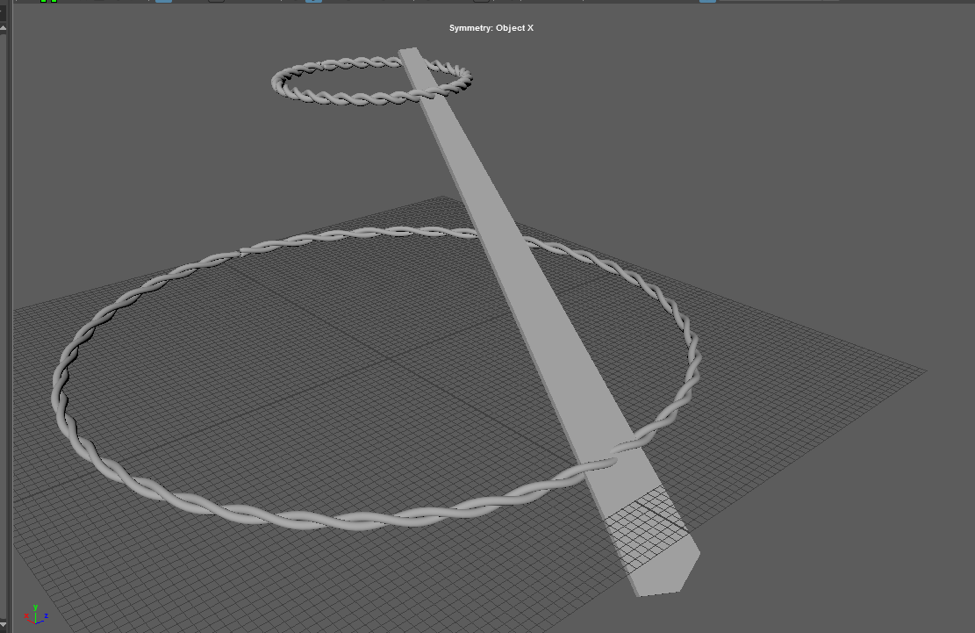

Figure 14: Extrusion and twisting of the smaller fish trap.

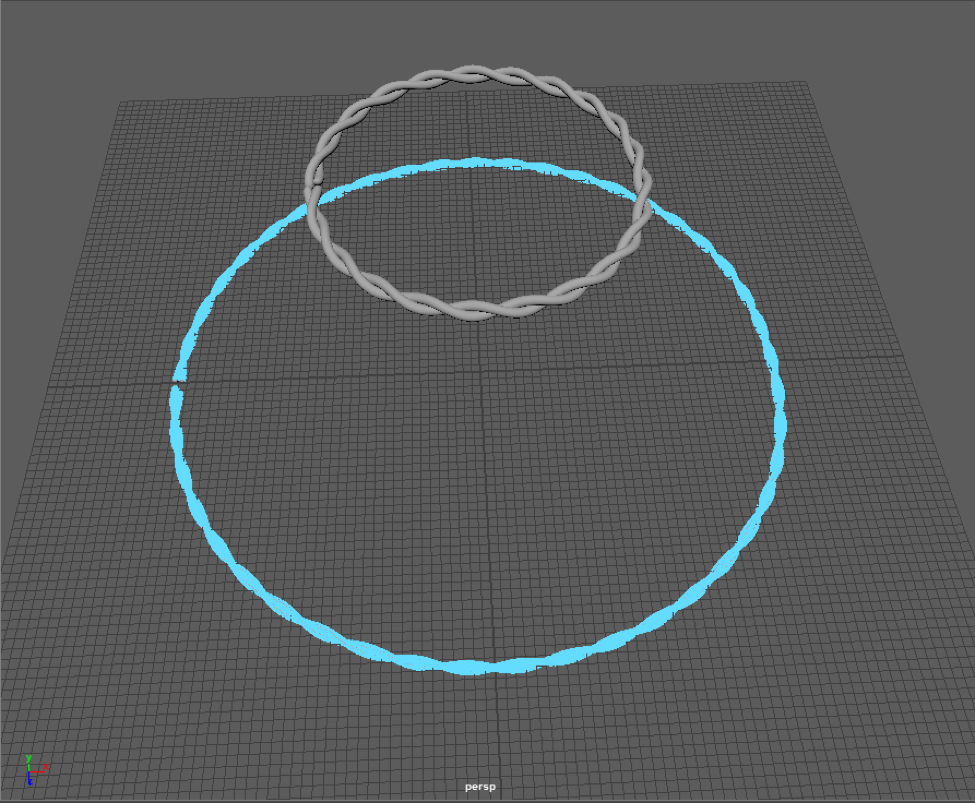

Figure 15: Creating the second ring.

Figure 16: Creating the plank that would be duplicated and rotated around the center axis. This polygon was cut from the basic shapes provided by Maya, and rotated into position.

Figure 17: The final cóvo (without texture)

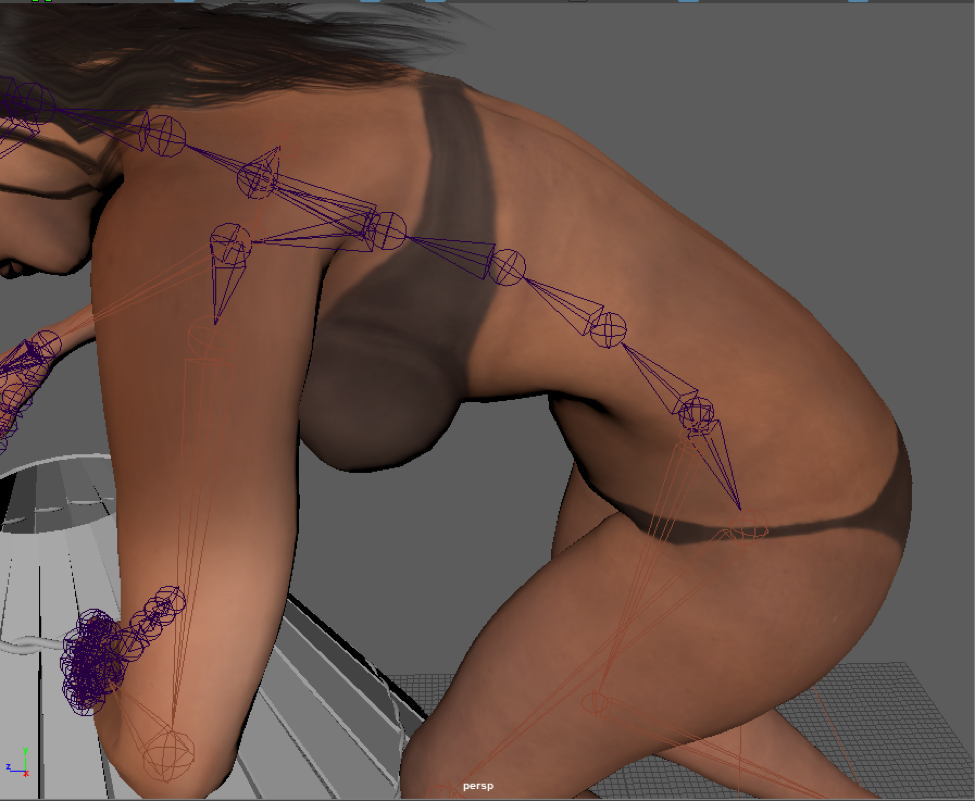

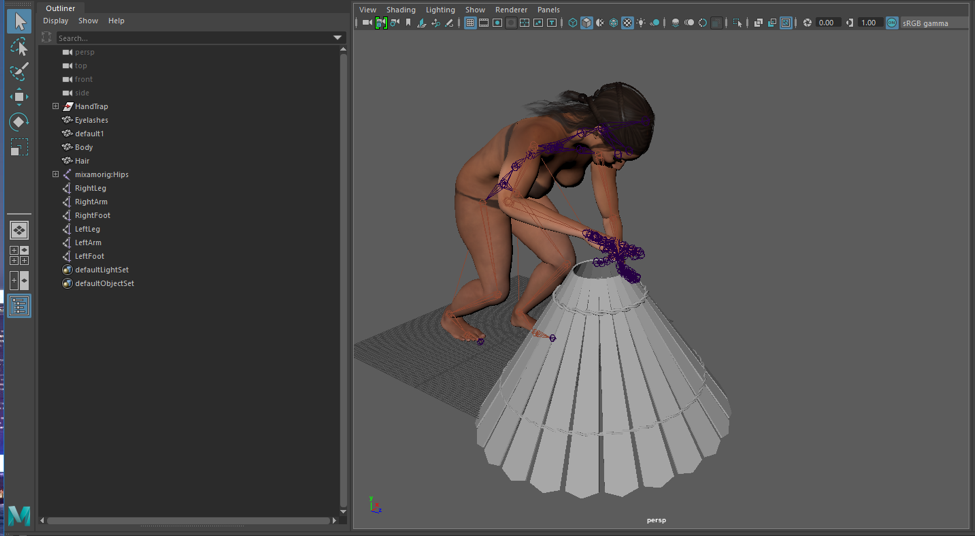

Figure 18: Changing the posture and spine of the digital model of a woman.

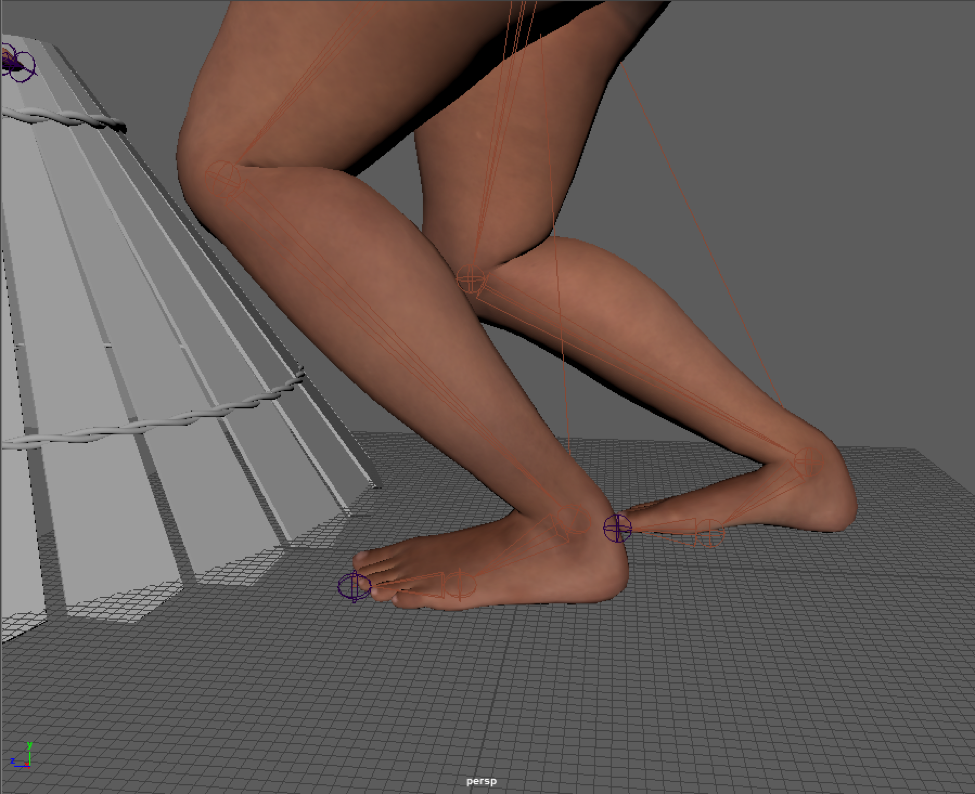

Figure 19: Changing the positioning of the feet of the digital woman model.

Figure 20: First attempt at using Maya to create an animation. The trap was placed too far away from the woman model, making it difficult to rotate certain joints to fit.

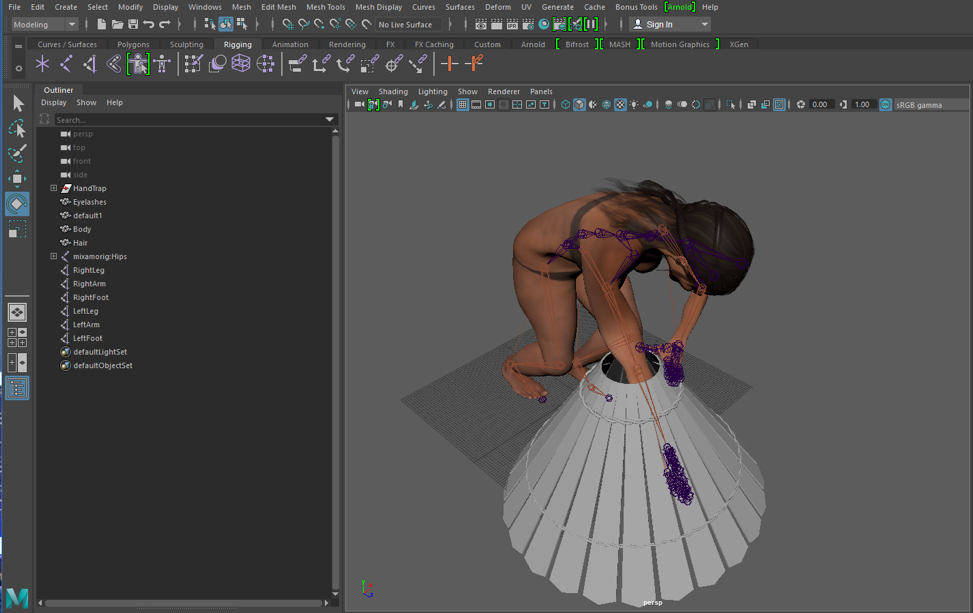

Figure 21: Adjusted the digital woman into a closer position. However, the hand would consistently clip through the trap.

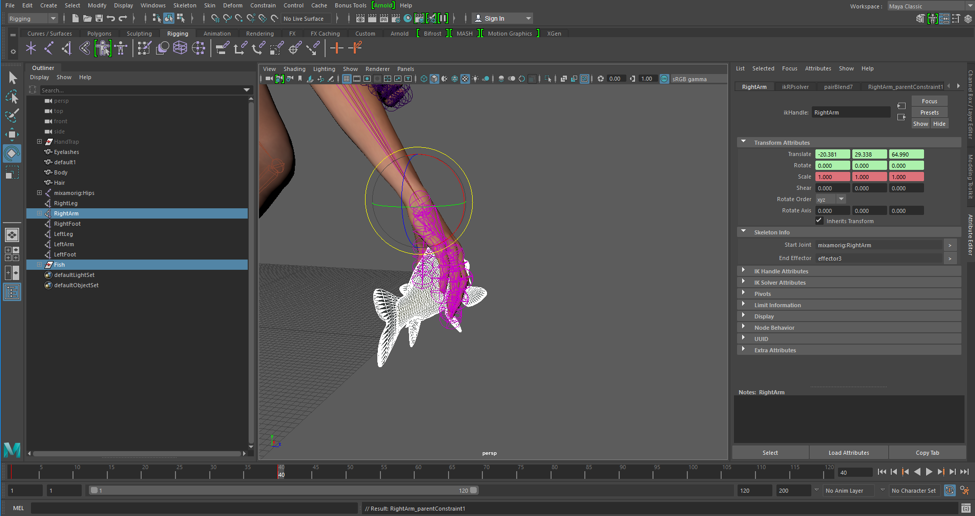

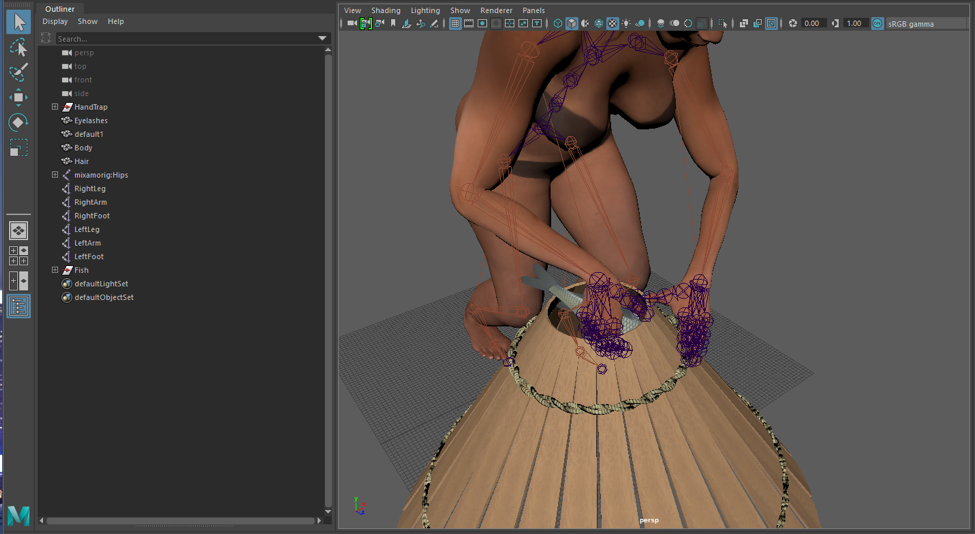

Figure 22: After further rounds of adjustment, creating parent restraints on how certain joints and grips would move, the model was coming into shape.

Figure 23: The clipping issue was final solved, and final textures were applied. There was now a smoother motion in the joints and the rotation of the body.

Figure 24: Pomacea shells found in the Bolivian Amazon (photograph provided by Clark Erickson).

Figure 25: Artwork depicting the Bolivian landscape during the flood season. The raised earthworks would form natural weirs, such as that seen in the center of the photograph. Natural ponds and lakes would form, such as that in center-right. (Killackey, Kathryn)

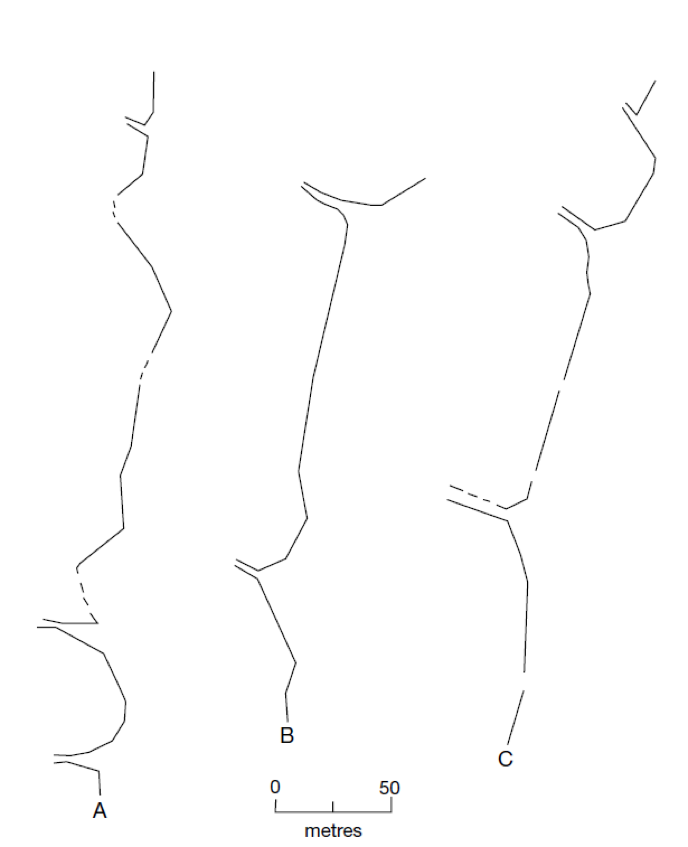

Figure 26: Plans of fish weirs. The small parallel openings are where large traps would fit (Erickson 2000: 193)