MODELING HAMMOCKS OF THE PRE-COLUMBIAN AMAZON

3D Models

Figures

Figure 1: Home depicting contemporary hammock usage in the Amazon, Yanonami peoples, Brazil (photograph by Robert Harding).

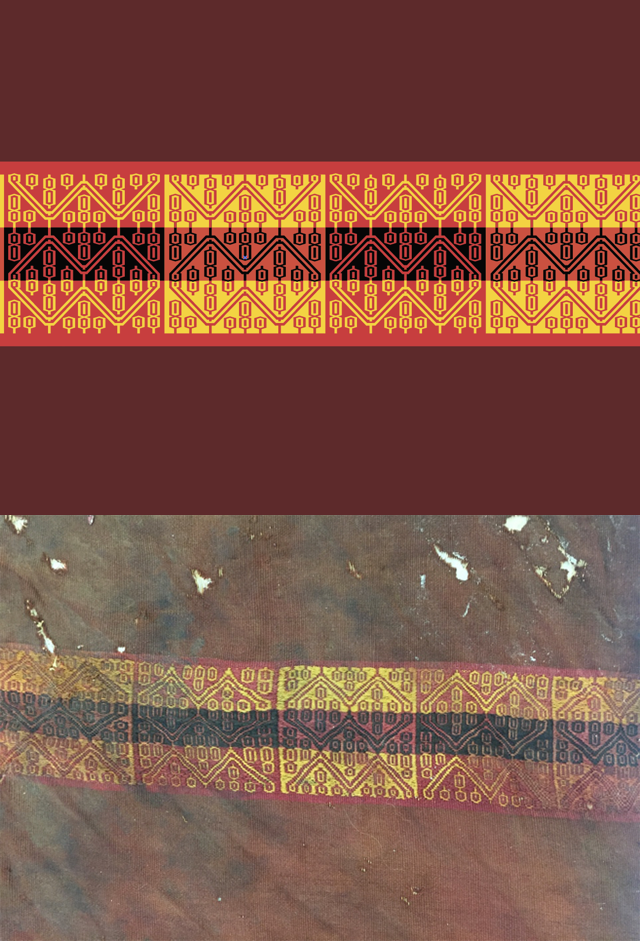

Figure 2:Pattern modeled in Adobe Illustrator (above) from tunic found in Penn Museum’s Amazon collection (below; culture unknown).

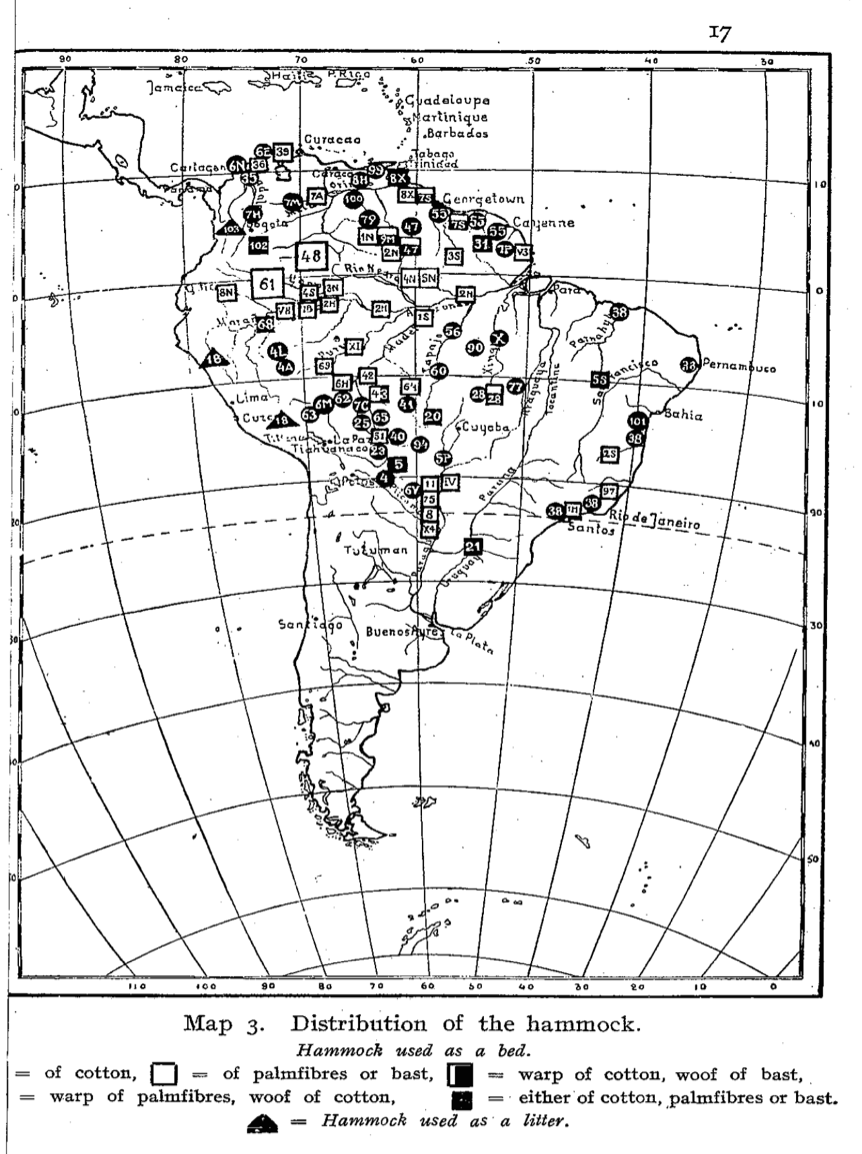

Figure 3: Distribution of the hammock used as a bed in South America (Nordenskiöld 1920:Figure 3).

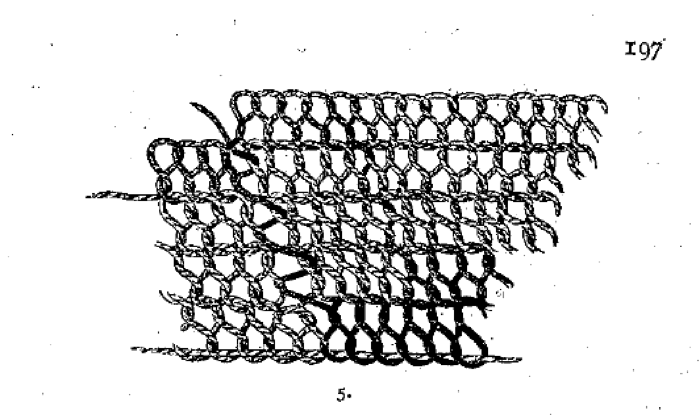

Figure 4: An example of a netted, “all-warp” hammock from the peoples of El Gran Chaco in Bolivia (Nordenskiöld 1919:Figure 60.5).

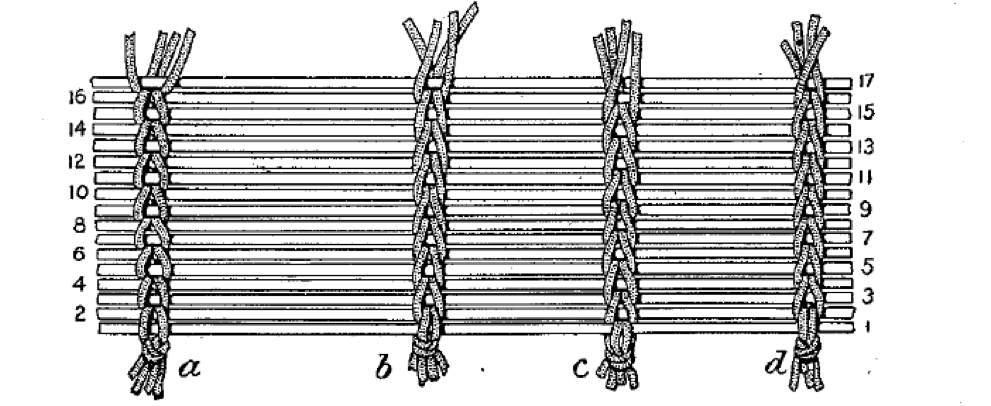

Figure 5: An example of a weft and warp hammock from the Carib and Makusi peoples of Central and South America (Roth 1916:Figure 198). The warps are the horizontal strings in this image, and the wefts are the interwoven, vertical bars.

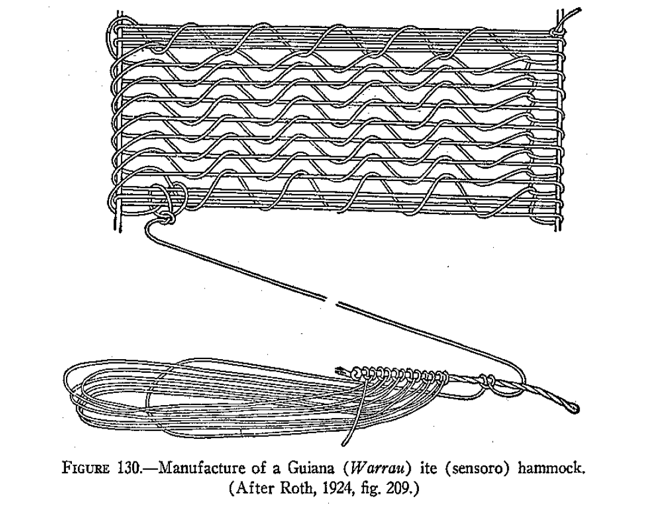

Figure 6: A netlike, warp hammock from the Warrau peoples of Guiana being made (Gullin 1948:Figure 130).

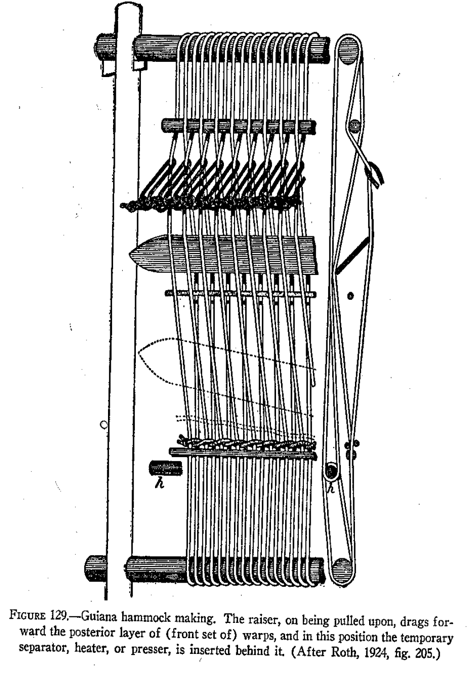

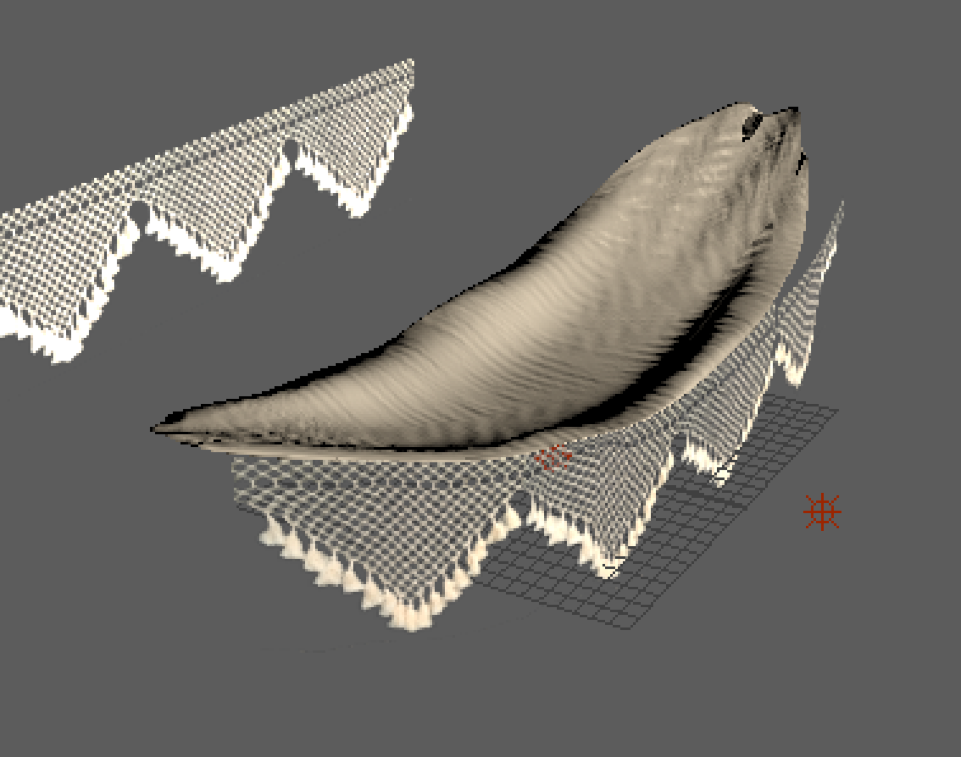

Figure 7: A weft and warp hammock from the Warrau peoples of Guiana being made with a loom (Gullin 1948:Figure 129).

Figure 8: A pressed specimen of Euglypha rojasiana, used to make yellow dye (Lowie 1948; Public Plant Archive of Brazil).

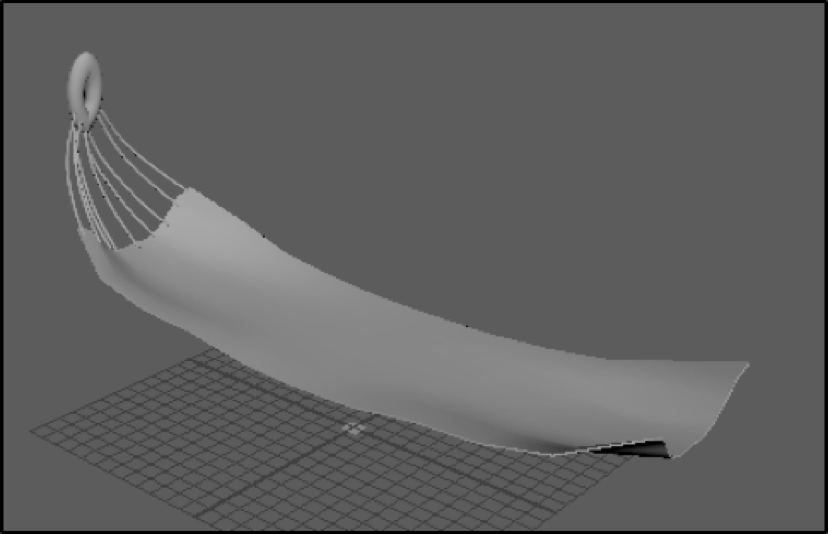

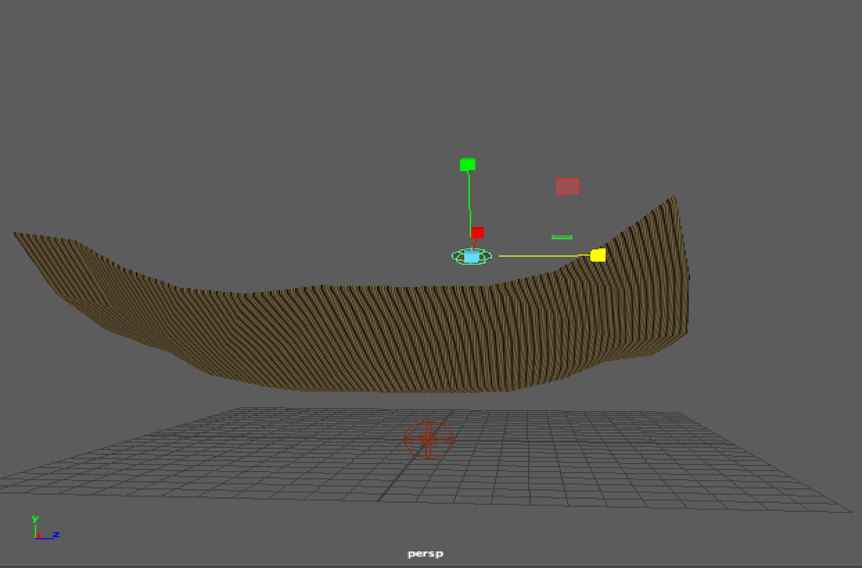

Figure 9: Early, flatter hammock shape, modeled using the soft-select tool and W-key. The widely space tying cords end in a thick loop.

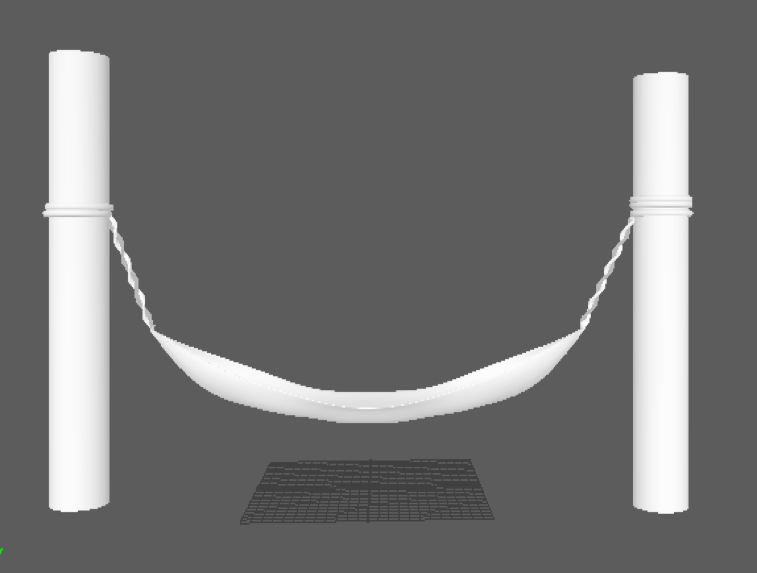

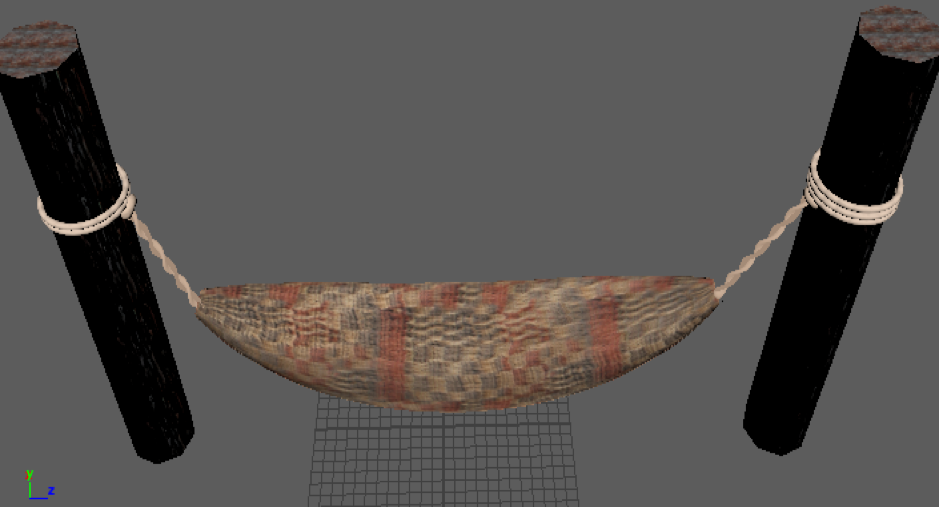

Figure 10: Final shape of the support beams, tying cords, and hammock without texture.

Figure 11: A sample of our results when searching for a rope texture map online. The dark black outline and perfectly rounded, smooth lines are inaccurate to the weaves we studied.A sample of our results when searching for a rope texture map online. The dark black outline and perfectly rounded, smooth lines are inaccurate to the weaves we studied.

Figure 12: An early hammock shape with the rope texture from online applied.

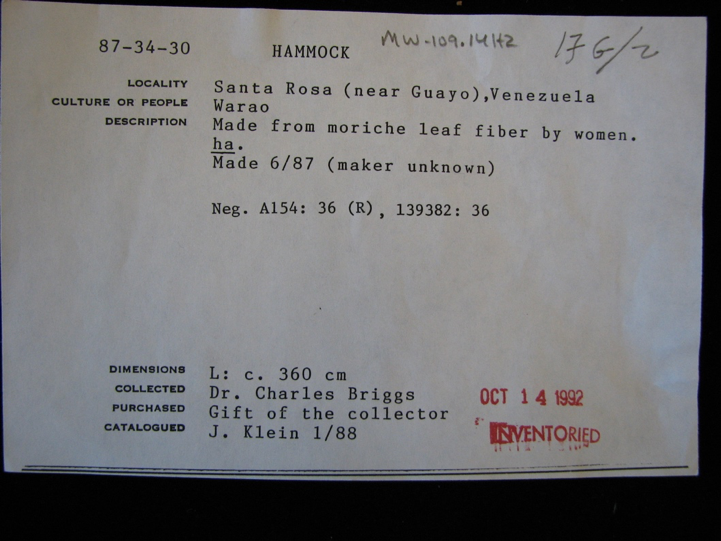

Figure 13: An all-warp, leaf fiber hammock from the Penn Museum’s Amazon collection, made by the Warao peoples of Venezuela.

Figure 14: Registrar information corresponding to Figure 13.

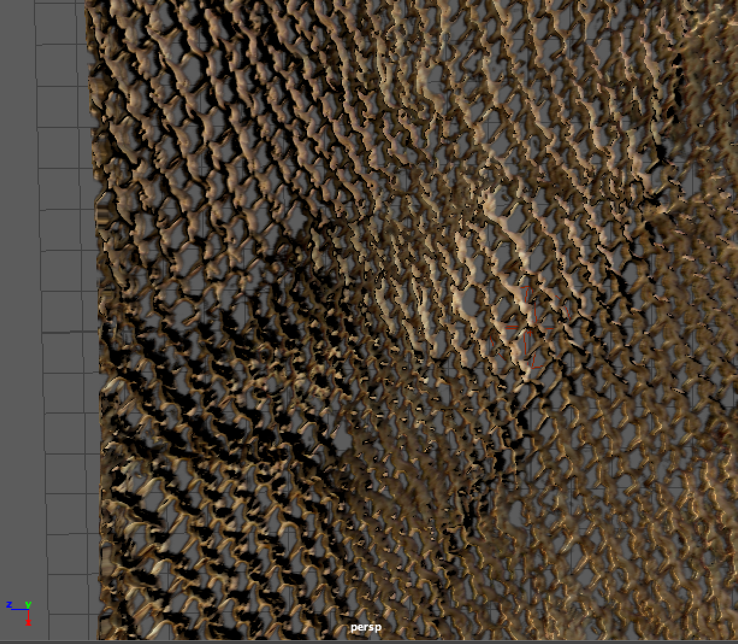

Figure 15: Hammock with texture, normal, and opacity maps applied responds to light.

Figure 16: Two layers of mapping create thickness and result in more dynamic response to light.

Figure 17: All-warp hammock body with maps applied.

Figure 18: A weft and warp hammock made by the Angayti peoples of Paraguay from the Penn Museum’s Amazon collection (material unknown).

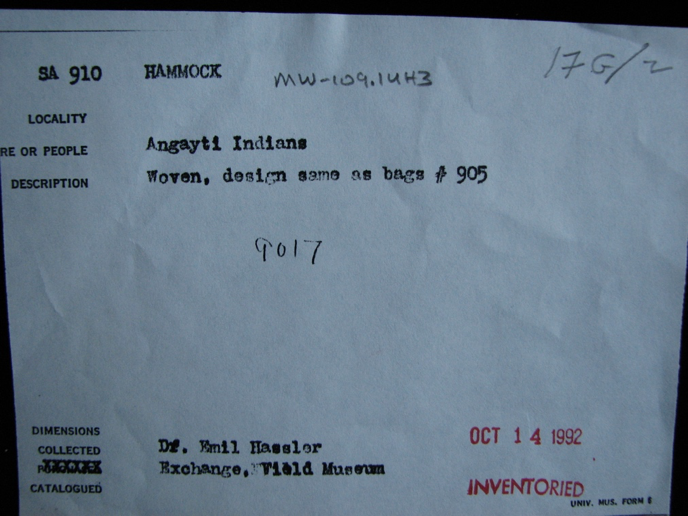

Figure 19: Registrar information corresponding to Figure 18.

Figure 20: Final model of weft and warp hammock with texture applied

Figure 21: Support beam with tiled wood texture and cords which suspend the hammock.

Figure 22: Weft and weave hammock made of cotton from the Guajira peoples of Columbia featuring an intricate fringe, a continuation of the wefts (photographed on December 7th museum visit with Clark Erickson).

Figure 23: The intricate fringe from Figure 22.

Figure 24: Photograph of intact fringe; used as texture map in Maya.

Figure 25: Opacity map of fringe created in Photoshop.

Figure 26: Fringe modeled in Maya

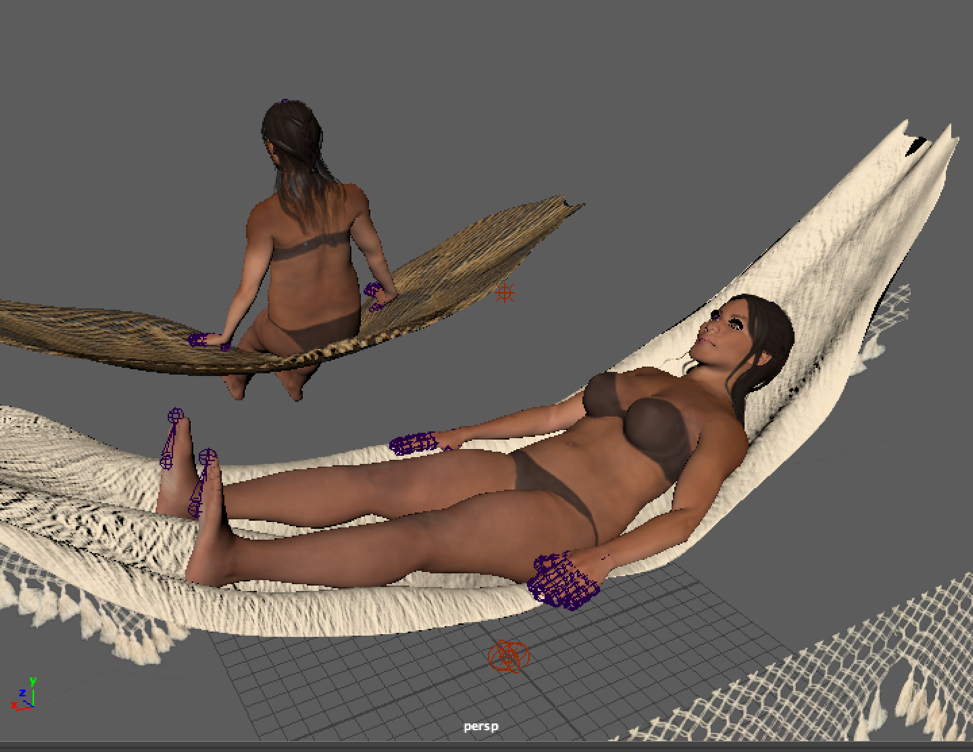

Figure 27: Final model of cotton, weft and warp hammock with fringe.

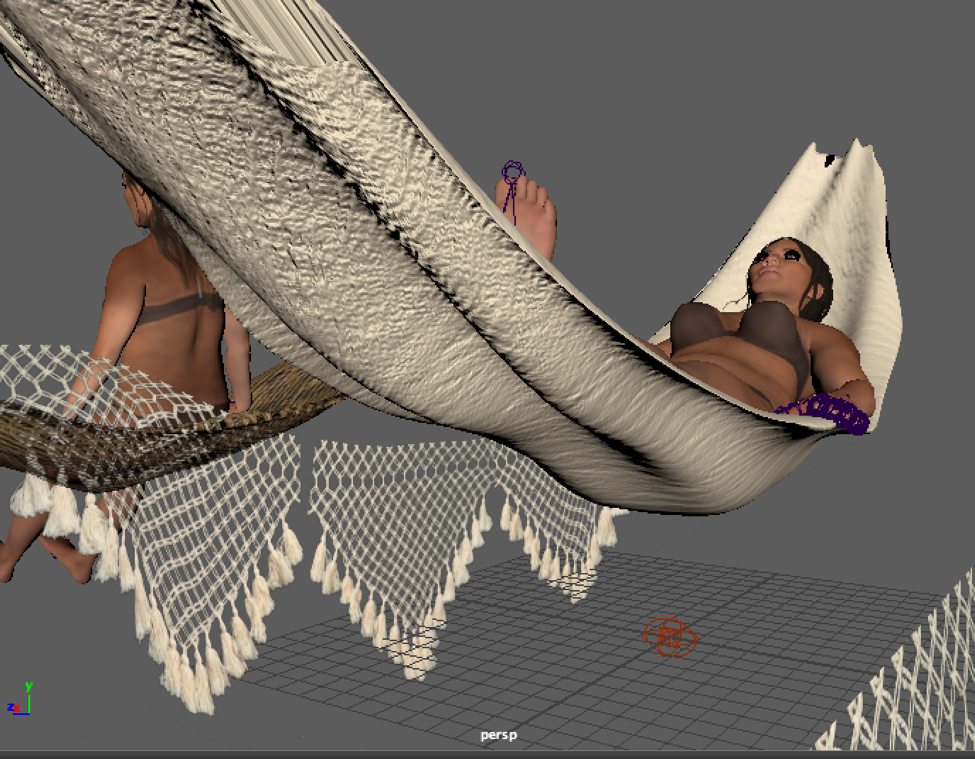

Figure 28: The hammock viewed from underneath forms to the woman’s legs and back.

Figure 29: Final model of woman sitting in hammock.

Final model of woman laying in hammock.

Figure 31: Final model from above